“How to Teach Science to the Pope” [Excerpts]

Reporter Michael Mason spent some time discussing the scientific policy and direction of the Roman Catholic Church with Brother Guy Consolmagno (a Vatican astronomer), other Catholic officials, and members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, a group that Mason describes as “a surprisingly nonreligious institution as well as one of the Vatican’s least understood.” Although the account begins with interesting research activities being undertaken, Consolmagno leaves little doubt as to what he considers the source of true authority.

“A hundred years ago we didn’t understand the Big Bang,” he says. “Now that we have the understanding of a universe that is big and expanding and changing, we can ask philosophical questions we would not have known to ask, like ‘What does it mean to have multiverses?’ These are wonderful questions. Science isn’t going to answer them, but science, by telling us what is there, causes us to ask these questions. It makes us go back to the seven days of creation—which is poetry, beautiful poetry, with a lesson underneath it--and say, ‘Oh, the seventh day is God resting as a way of reminding us that God doesn’t do everything.’ God built this universe but gave you and me the freedom to make choices within the universe.”

Before moving on, it is important to stop and consider what the lesson “underneath” a poetic interpretation of Genesis would be. If Genesis is not the literal account of God’s creative actions, then does that mean that God is deceptive? After all, if we are to read Genesis as a poetic rendering of the big bang, then the order of creation would be completely wrong. For example, in the big bang model, stars existed before the earth, but God’s Word emphatically tells us that the earth existed first. That’s quite a big error. So, is God’s supposed message in a “poetical” rendering that He doesn’t know how He created?

The author of the article rightly points out what this implies (and points out how compromise weakens a Christian’s witness): “When science posits a truth that seems to contradict Scripture (lack of evidence of a global flood, for example), the Bible’s inherent elasticity simply envelops the new finding, and any apparent contradiction is relegated to the realm of parable (where Noah’s ark resides, in the view of many Catholics).”

If the Bible is not the starting point, as it is not for many in this article, then anything can be tossed out when there are “convincing reasons.” However, this argument is flawed in many ways. First, naturalists would say that there are “convincing reasons” to assume that Christ could not have physically risen from the dead, since that is not possible in a naturalistic framework. But if that’s the case, if He did not physically rise from the dead, then we are all dead in our sins, and those quoted in this article have a worthless faith that cannot save them (1 Corinthians:15:12Now if Christ be preached that he rose from the dead, how say some among you that there is no resurrection of the dead?

See All...–19). Second, what if the “reasons” for rejecting what the Bible teaches turn out to be wrong? For example, there are many geologists who do unequivocally see evidence of a global Flood in the millions of dead things in rock layers all over the world. They, too, are scientists, but they are ignored simply because they do not toe the Darwin party line. Finally, if God did not mean what He said in the Bible, if He spoke in such a way that the “interpretation” can change with the winds of current thought, then what good is the Bible to us? There may be “moral lessons” hidden in the parts that conflict with what “science” tells us, but who decides what those moral lessons are? Do they simply shift along with what humans assume is best? Is God really God if He can’t speak clearly enough that we can understand Him or if He doesn’t provide concrete, unchanging truth?

http://www.answersingenesis.org/articles/2008/08/23/news-to-note-08232008

How Close Are We?

How Close Are We? 101 Last Days Prophecies

101 Last Days Prophecies 101 Scientific Facts

101 Scientific Facts Revelation 13 - Satan's Last Victory

Revelation 13 - Satan's Last Victory TULIP and the Bible

TULIP and the Bible Charting the Bible Chronologically

Charting the Bible Chronologically Berean Bite: Calvinism Set

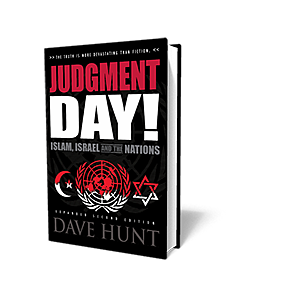

Berean Bite: Calvinism Set Judgment Day!

Judgment Day! Gospel Transformation

Gospel Transformation False Christ Coming - Does Anybody Care?

False Christ Coming - Does Anybody Care?